Once upon a time, February used to be the humid month in Sydney. You could pretty much guarantee the humidity would be layered upon a hot Sydney summer, bang on February 1st. Then spot on March 1st, the humidity would lift and we’d get back to enjoying our weather again.

But, over the past 10-15 years, the humidity has spread its wet sticky tentacles all the way out from November through to April.

I’ve written before about running in hot weather, how it impacts your performance, what you can do to minimise drops in performance, and how to pre-cool before training and events. All of that is relevant for running in humidity as well, so make sure you check those articles out if you’re struggling a bit running in this weather.

Why is it harder running in humidity?

Listen to this Hooked on Running Radio episode on hot and humid running

When you layer humidity on top of the heat, it adds a whole new dimension to the discomfort level when you are running, or doing anything more energetic than kicking back at the beach.

What we commonly refer to as humidity, is actually a measure of relative humidity. It is the amount of moisture in the air, as a percentage of the maximum amount of moisture the air can hold. 100% humidity is when the air is at its maximum moisture capacity. And here’s the kicker. Hot air can hold more moisture than cold air.

At -40C, no more than 0.2% of the air can be water molecules. So if 0.2% of the molecules that make up the air are water molecules, then relative humidity would be 100%. At +30C, the moisture carrying capacity of the air is 4%. So at 100% humidity, at +30C, the air will consist of 4% water molecules, plus the other molecules that make up air (nitrogen and oxygen mostly)

70% humidity, would mean that the air is carrying 70% of the moisture it is capable of holding.

How does humidity impact running performance?

Your body sweats to cool down. Sweat evaporates off the skin, providing a cooling effect. At high levels of relative humidity, it is harder for the moisture on your skin to be absorbed into the air. There is a limited amount of moisture the air can hold. At high humidity, it is already holding a lot of moisture, so doesn’t have the capacity to absorb as much from your skin. Hence, the body’s natural cooling mechanism doesn’t work very well when you’re running in humidity.

And that has implications for performance, and how you feel. Mostly, our bodies operate with a core temp of around 36.5-37 degrees C. If that core temp rises to around 39C, your body will start diverting blood to the skin to keep it cool. That decreases the amount of blood going to working muscles. That means your muscles will not be receiving as much oxygen, (as it is blood which carries oxygen around the body). Oxygen is needed for the release of energy in the muscles, so when your core temperature heats up, your working muscles literally don’t have as much energy, leaving you feeling fatigued, or at the very least, sluggish.

If your core temperature creeps up another degree or so to around 40C, your brain will start to inhibit the recruitment of muscles fibres, to stop you from doing yourself damage. Fewer muscle fibres will be available to move your limbs, so moving will feel much harder.

Why is it harder to breathe when you are running in humidity?

Most people, if not acclimatised, find it harder to breathe in humid conditions. This is particularly so if you have a respiratory conditions such as asthma.

A given volume of gas, at any given temperature and pressure, will hold a set number of molecules. That number cannot vary. Dry air is made up mostly of oxygen and nitrogen. As humidity increases, and more water molecules are suspended in the air, some of the oxygen molecules are shunted out of the air to make way for the moisture. There is less oxygen in air with high levels of humidity, than in dry air, so if you feel like you are struggling to get in enough oxygen in hot humid conditions, you are!

A study in Nepal compared physical performance of residents living in hot humid conditions at sea level, with that of people livning at an altitude of 3800m. Not super high, but high enough for you to feel it if you are not used to living at altitude.

The researchers concluded that the hot humid conditions at sea level negatively impacted performance as much as the low oxygen levels at high altitude. If you’ve been at that level of altitude or higher, you’ll know you have to work a lot harder to get things done, than you do at sea level.

Here are a couple of videos which show the impact altitude can have on your breathing. The first is me at 4600m. We’d been walking all morning, but had been pretty much at rest for 10 minutes – as much as bossing my husband around and telling him how to video can be considered resting!

This video is that very same husband after running about 100m up a slight rise, at 5300m. You can see he’s struggling to keep his breathing under control whilst he’s talking.

Impact of humidity on asthma

If you have asthma, you get the double whammy. Breathing hot humid air can trigger airway resistance in people with asthma, as well as triggering coughs. Even if your asthma is generally only mild, it’s a good idea to take some preventative measures before running in hot humid conditions.

Using dew point, or “feels like” temperatures to schedule your training

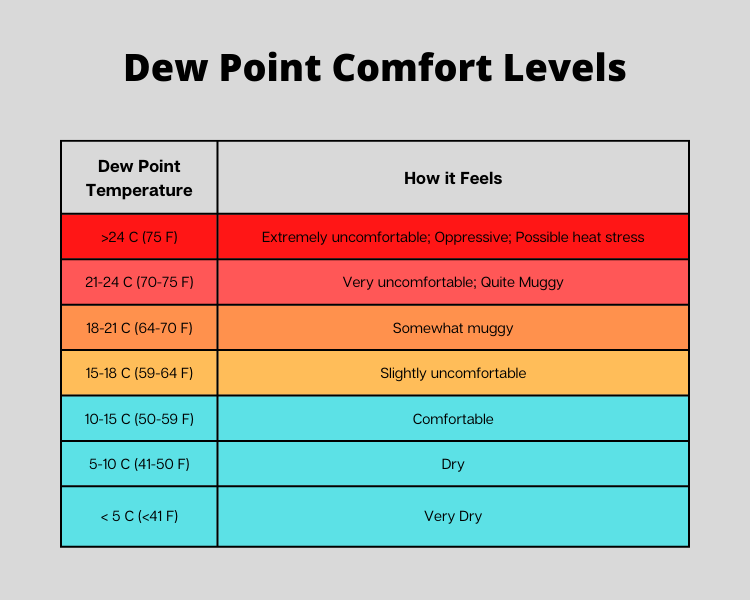

The dew point is the temperature to which the air needs to cool for dew to form. It represents how much moisture is in the air. A higher dew point temperature indicates there is more moisture in the atmosphere, which will influence the way you feel. If you look at the dew point, rather than the temperature or the humidity alone, then you’ll get a better idea of when it will be more comfortable to run.

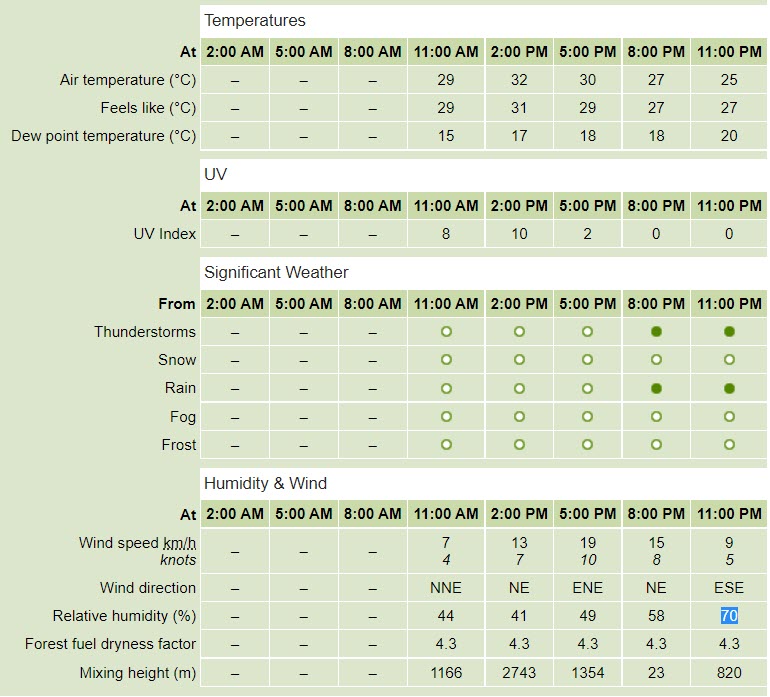

Have a look at this detailed weather forecast. You can see this info by searching on detailed forecast and your location – eg “Sydney detailed forecast” in the search box on the Bureau of Meteorolgy site.

You can see that it will be 32C at 2pm, with relative humidity of 41%. AT 11pm, the temperature drops to 25C, but relative humidity rises to 70%. The dew point at 2pm will be 17, whilst the dew point at 11pm will be 20. With the higher dew point later in the night, it might actually be more uncomfortable running than it would be at 2pm. I’d put a caveat on that – if you were running in the sun at 2pm, I think you would still find it more uncomfortable running then, than later.

Looking at dew point and the feels like temperature can give you a good idea of when will be a better time to run. Don’t forget to look at the UV index as well. (Though you don’t have to be Einstein to know that the UV index in the middle of the day will be higher than 11pm)

I don’t mind a humid run, but if you really find running in humidity difficult, plan for a race in the less humid months for peak performance.

Edt: Just spotted this article on Sydney’s record humidity in January 2022- Sydney Morning Herald

References:

“Influence of relative humidity on prolonged exercise capacity in a warm environment”