An article published recently in the BMJ argues that we have been pursuing the wrong hypothesis on the causes of obesity. Along with substandard science, this wrongheadedness has apparently exacerbated the obesity crisis.

Author Gary Taubes asserts that obesity is probably not caused by a positive energy balance (more energy is consumed than spent). A promising rival hypothesis has been forgotten without having been properly investigated.

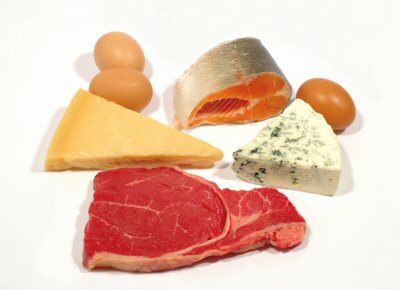

According to that hypothesis, obesity is a hormonal, regulatory disorder. Energy imbalance is only a consequence of that underlying hormonal factor. The problem is not that we’re eating too much, it’s what we’re eating. And the probable culprit is carbohydrates. But this is yet to be definitively proven.

Enter the Nutrition Science Initiative (NuSI), a US-based not-for-profit organisation co-founded by Taubes that will fund the rigorous experiments needed to “find out, once and for all, what we need to eat to be healthy”.

NuSI will also “re-introduce a culture of rigorous experimental science to the field of nutrition.” A condition for meaningful progress in this field is apparently “a refusal to accept substandard science as sufficient to establish reliable knowledge, let alone for public health guidelines.”

So, out with the research done to date, and away with current guidelines, right?

Who speaks and for whom?

Actually, not so fast. Let’s first examine who wants us to forget everything we know and postpone all action on obesity. Taubes is a journalist and author, not a scientist. And his organisation, NuSI, is financed by the “Giving Library”, which “offers philanthropists an innovative way to enhance their strategic charitable giving”. It also gives would-be donors a “forum for anonymous communication”.

The NuSI board of advisors “all share a passion and belief: to date nutrition science has been inadequate in drawing conclusions and making sound recommendations.” The board of directors are people with backgrounds in consultancies, corporate health care and private investment management.

Anonymous donors, claims of a scientific establishment suppressing ideas, claims that the science isn’t settled and no action should be taken, that more research by “independent, sceptical researchers” is needed, the involvement of big corporate actors in a field where research findings can have consequences for a multibillion-dollar industry – where have we seen all that before?

It smacks of denialism. But Taubes states that NuSI doesn’t accept support from the food industry, there are no food industry representatives on any NuSI board and taking aim at carbohydrates probably doesn’t make you friends in large sections of that industry. Perhaps this is just the way you raise funds for research in contemporary America.

But is it true that all the research in the field to date has uncritically accepted energy imbalance as the cause of obesity? And that no-one has yet looked at hormones as a cause of obesity? The short answer is no. While Taubes presents his ideas as revolutionary, they are actually fit quite comfortably in a long tradition of low-carb dieting. And it’s not true that such diets have never been scientifically tested.

To support his argument, Taubes cites a study that compared the Atkins diet to other diets, and found it achieved greater weight loss. That could mean carbohydrates are causing weight gain, but it could also result from the fact that carbs are the biggest part of our diets and restricting their consumption leads to overall reductions in caloric intake.

Whatever the case, it’s customary to do the research first and claim that you have found the cause of obesity (if indeed you have) second, rather than the other way around as Taubes seems to be doing. But again, this may be the way to raise funds for research in America.

Missing the bigger picture

Someone reading Taubes’ article might be forgiven for believing that the current thinking about solutions stops at the individual level and is all about diets and exercise. Not once does Taubes mention the “obesogenic environment”, which many obesity researchers consider to be the cause of the obesity epidemic.

Where many researchers focus on our changing living environment, Taubes puts the focus squarely on hormonal factors. But these probably haven’t changed while obesity rates soared. And he asks if we can all please wait for the results of this revolutionary research before taking any action.

That’s not helpful. We have a problem now, and contrary to Taubes’ claims, we do know something about its causes.

If Taubes believes increased consumption of carbohydrates is the cause of the obesity epidemic, he might have pointed to a trial that shows that replacing sugar-containing drinks with non-caloric drinks reduces weight gain and fat accumulation in children. Also, why not support calls for limits on advertising and availability of sugar-sweetened beverages, and for increased taxation to reduce consumption?

Taubes exaggerates the uncertainties in current nutrition science. There’s support for a causal role of carbohydrate-rich diets in the obesity epidemic but, as he notes, such diets also tend to be rich in calories. He is yet to conclusively prove it’s the carbs specifically that are to blame.

So rather than wait years for the results of NuSI-funded research, we should change our food supply to discourage excess sugar intake. A tax on sugar-sweetened beverages would be a good start, as would restrictions on advertising to children.

Lennert Veerman receives funding from NHMRC and ARC.

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.