You’d be hard pressed to find someone who has never experienced a stitch before, yet despite this, to date, we are still not sure what causes stitches, nor how to prevent them. Not what you wanted to hear, I know!

In the literature, stitches are known as Exercise-related Transient Abdominal Pain (ETAP). According to researchers Morton and Callister, 70% of runners experience stitches, and in a running event, 20% of participants can expect a stitch. (2)

What Do We Know About Stitches?

- Side stitches can range from a dull ache to a crampy stabbing feeling, or a pulling sensation

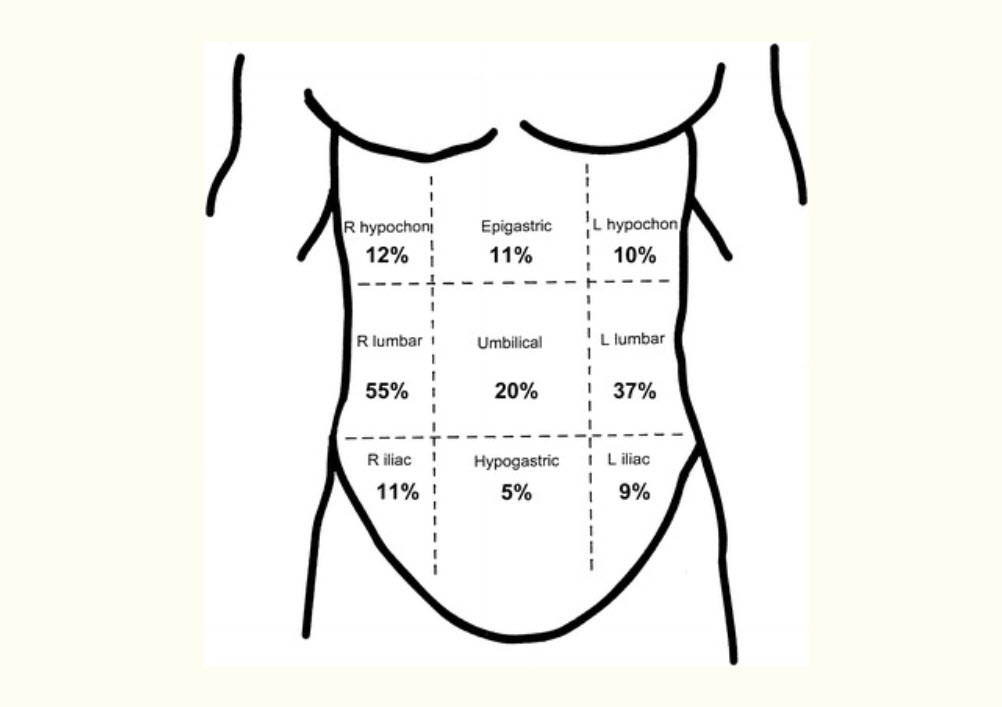

- They occur most commonly on the right side in the middle third of the abdomen, adjacent to the navel

- The next most common area is in the left, middle area of the abdomen

- The next most common area is around the navel

- Around a third of people report non-injury related shoulder tip pain (STP) associated with stitches

- The prevalence, severity and frequency of stitches decreases with age

- BMI does not affect prevalence and frequency of stitches, but athletes with higher BMI have reported more localised stitches, and more severe

- Men are more likely to report a stitch as an achy type of pain, and women report it more as a stabbing, sharp pain

- The frequency of stitches seems to decrease with frequency of training, but frequency of training has little effect on severity or prevalence of stitches.

- The frequency and severity of stitches seems unrelated to number of years of training and training volume

- Athletes of all levels, from inexperienced to elites are just as susceptible to getting a stitch, however elite athletes will tend to have fewer stitches

What Don’t We Know About Stitches?

Exactly what causes them, and therefore how to prevent and treat them!!

Some Theories on What Causes Stitches

Diaphragmatic Ischemia

More simply put, limited blood supply to the diaphragm.

This would account for some of the things associated with stitches like shoulder tip pain. The diaphragm is mostly innervated by the phrenic nerve, which refers pain to the shoulder tip region. The outside portions of the diaphragm are innervated by other nerves which could account for the sharp and localised pain in the region just below the ribs.

But the evidence against this theory is quite strong. Stitches are reasonably common in activities that don’t demand a lot of the respiratory system, such as horse riding and off road car racing, so a lack of blood supply to the diaphragm is not very likely.

Also, it is very unlikely that the blood supply to the diaphragm would be limited, whilst blood supply to the working muscles would not be limited. The good functioning of the diaphragm is more important to sustaining life than is the use of the legs and arms for running, so the brain is more likely to shut off supply of blood to the working muscles before blood supply to the diaphragm shuts off – as a working diaphragm is necessary for breathing, therefore life!

Mechanical Stress on Ligaments Associated with Organs

Some of the organs in the abdomen, of note the liver and stomach, are supported by ligaments that attach onto the diaphragm. One theory on the causes of stitches is that there is mechanical stress on these ligaments, causing pain.

This does explain why you can get a stitch in activities that have a jolting nature but low demands on the respiratory system, such as horse riding. Also, eating and drinking prior to exercise could cause a stitch by the increase in the mass in the digestive system loading the ligaments that support the stomach. Also, when you take in beverages with a high sugar content, you increase your risk of a stitch. Higher sugar content drinks (over about 10% carbs) can slow down gastric emptying, causing the fluids to stay in your stomach for longer, and therefore put more stress on the ligaments supporting the stomach.

But… this theory does not account for stitches lower in the abdomen, nor does it account for the fact that increased BMI, which would likely put more stress on those ligaments, does not correlate with an increase in the prevalence of stitches. And another nail in the coffin for the mechanical stress theory. Pain arising from these ligaments would be likely to be similar to pain related to organs, which is usually dull, and diffuse. The pain of a stitch is more often localised and sharp.

Gastrointestinal Disturbances

The main reason stitches have been thought of as a gastrointestinal problem is because they have been associated with eating prior to exercise. But, the pain is also commonly felt when nothing has been consumed several hours prior to exercise. Typical pain of gastrointestinal problems usually results in writhing movement to try to get relief from the pain, whereas with stitches, reducing movement and/or pressing on or massaging the area of pain has been reported to help. So the pain patterns of a stitch aren’t consistent with gastrointestinal problems.

Muscle Cramp

In a couple of large studies, 25% of stitch sufferers described the pain as “cramping”, which led to subsequent studies which measured localized electromyographic (EMG) activity while a stitch was present. Muscular cramps are associated with high levels of EMG activity . EMG activity was not elevated at the site of the stitch during an episode of the pain, which means the muscle cramp theory is also a no go.

Pain Causes By Nerves

This one does have some legs.

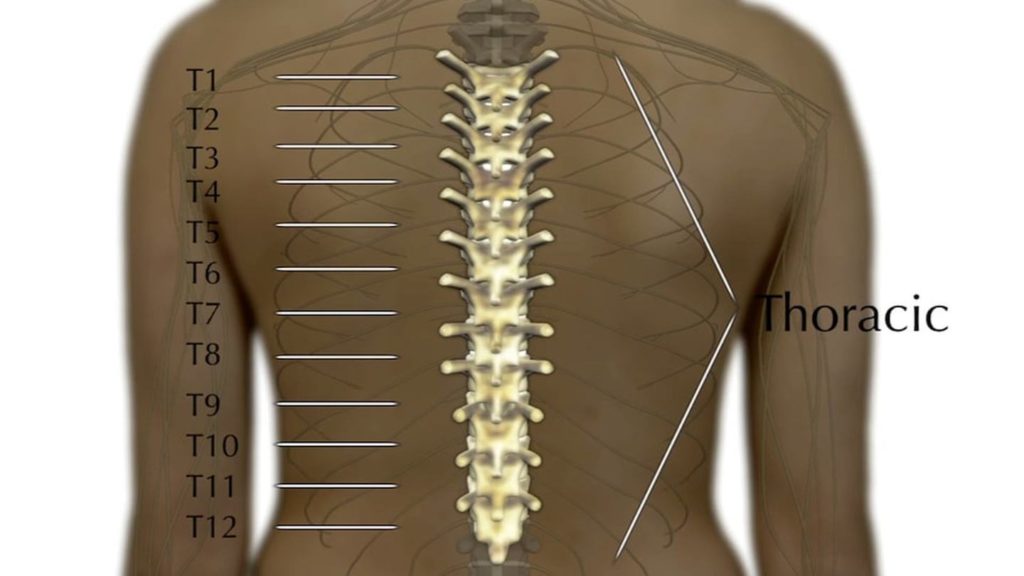

It does seem that stitches can be affected by poor posture, particularly in the thoracic region. That’s the mid region of the back, between your neck and your lumber region (the lumber region is the bit above your backside that curves inwards).

It’s been found that putting pressure on the vertebrae in this region of the back, specifically T8-T12, which innervates the abdominal wall, can reproduce symptoms of a stitch. In one study, a stitch could be exactly reproduced in 8 out of 17 people assessed, and the site of pain corresponded to the nerve root being pressed.

Other cases of stitch-like symptoms where the nervous system is implicated include slipping rib syndrome which results in trauma to the adjacent nerve, abdominal wall nerve entrapment, and spinal tumours and facet joint cysts which cause compression of the nerves of the muscles between the ribs (intercostal nerves).

Intercostal nerves can also be vulnerable to compression as a result in the reduction of the height of the discs between the vertebrae – something that can happen with the dynamic and repetitive movements of the torso in running.

Irritation of the Parietal Peritoneum

Stay with me on this one.

The parietal peritoneum is a layer of tissue that adheres to the abdominal wall.

The visceral peritoneum are layers of tissue lining the abdominal organs.

The peritoneal cavity is the potential space that separates the abdominal organs and parietal peritoneum. The cavity is filled with fluid to prevent friction between the 2 layers

Increased friction between the two might be a cause of the stitch. This increased friction could be caused by the distension of the stomach post-meal. Also, changes in the thickness and quantity of the fluid in the peritoneal cavity during exercise could cause an increase in friction.

Poor Functional Core Stability

A 2013 study of 50 runners found that those runners who did not experience stitches had stronger transversus abdominis muscles, than those who reported experiencing stitches either weekly or yearly (though interestingly, not than those who experienced stitches monthly). The transversus abdominis muscle is a deep muscle important for stabilising the lumbar spine and pelvis. Those who did not experience stitches had significantly thicker resting transversus abdominis muscles. Better core strength and activation of the muscles of the abdomen could lead to the lessening of symptoms of a stitch.

How to Prevent Side Stitches Whilst Running

Eating and Drinking

Don’t have foods and drinks before your run that are likely to stay in your stomach for a long time. Avoid highly sugary drinks (greater than 10% carbs) and avoid foods high in fat and fibre. If you’re taking gels or other energy boosters, make sure you are taking in water, to reduce the concentration of sugar.

Strength Training

Core strength and conditioning is important for everything we do, so even if it doesn’t stop you from getting a stitch, you should be trying to improve it! But, it does seem that improving your core strength, and improving your posture with stretching and strengthening exercises can help if you are a chronic stitch sufferer.

Improve Your Fitness

The frequency of stitches reduces with higher fitness levels, so getting fitter could help to mitigate the problem.

Get Older

The prevalence of stitches reduces with age, so you could just sit back and wait!!!

Immediate Treatment For Stitches

Unfortunately, the best way to stop as stitch is to stop doing whatever activity is causing it. That is rarely practical.

The most common techniques to get rid of a stitch reported by sufferers in a large study off 600:

- The most common techniques to get rid off a stitch reported by sufferers in a large study off 600,:

- Deep breathing – reported by 40% of suffers

- Pushing on the affected area (31%)

- Stretching the affected side (22%)

- Bending over forwards (8%)

Other techniques include:

- Breathing shallowly

- Forcing out and sucking in between clenched teeth

- Bracing the abdominal muscles – my personal favourite. It does seem to stop you from feeling the stitch whilst you’re bracing, but once you stop, it has a tendency to come back.

References

- Morton DP, Callister R. Characteristics and etiology of exercise-related transient abdominal pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(2):432–438. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00026.

2. Morton DP, Richards D, Callister R. Epidemlology of exercise-related transient abdominal pain at the Sydney City to Surf community run. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(2):152–162. doi: 10.1016/S1440-2440(05)80006-4.

3. Morton DP, Richards D, Callister R. Exercise-Related Transient Abdominal Pain (ETAP) Sports Med 2015; 23–35.Published online 2014 Sep 3